Scroll down to see a selection of etchings, read excerpts, hear a song in Ladino, or listen to an interview with Radio Sefarad Madrid.

TO ORDER TRACES OF SEPHARAD, CLICK ON “SHOP (GFP).”

The Book

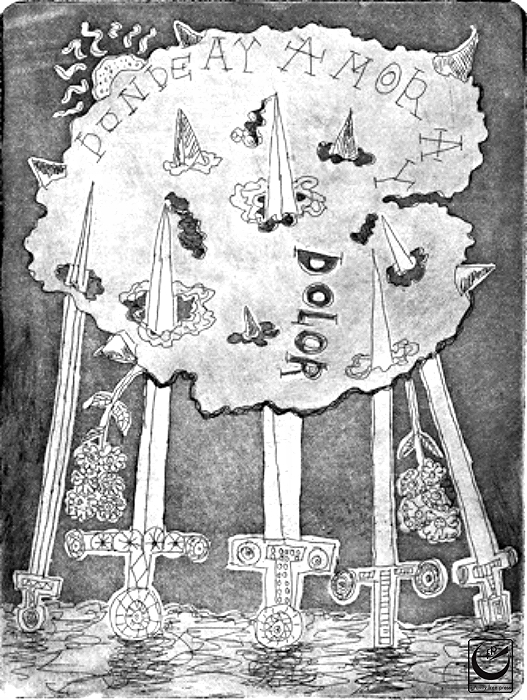

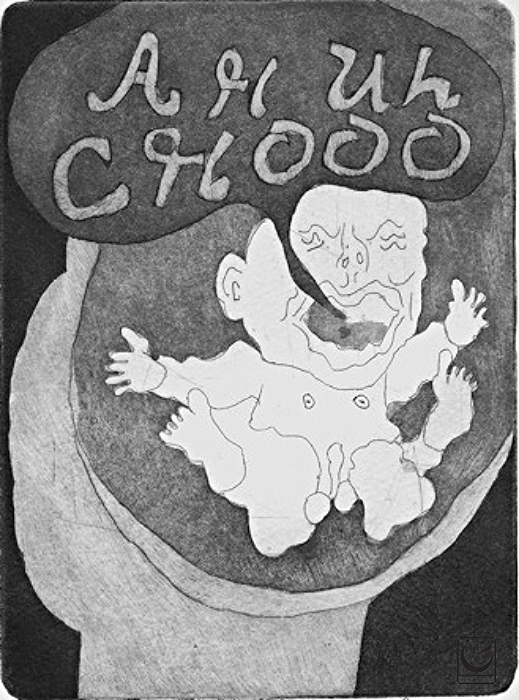

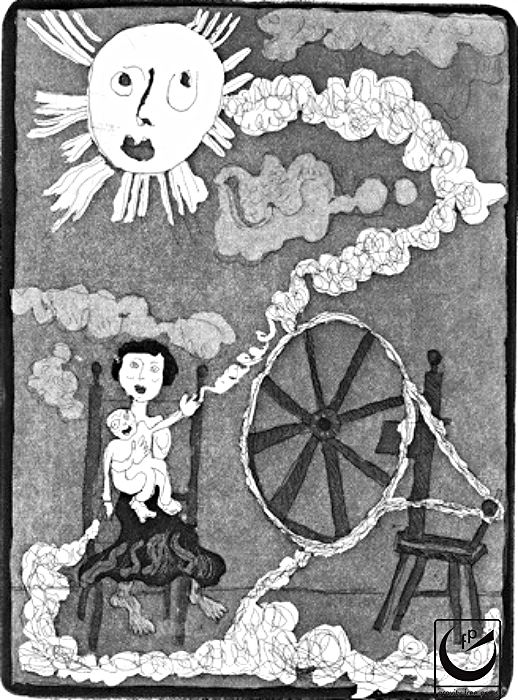

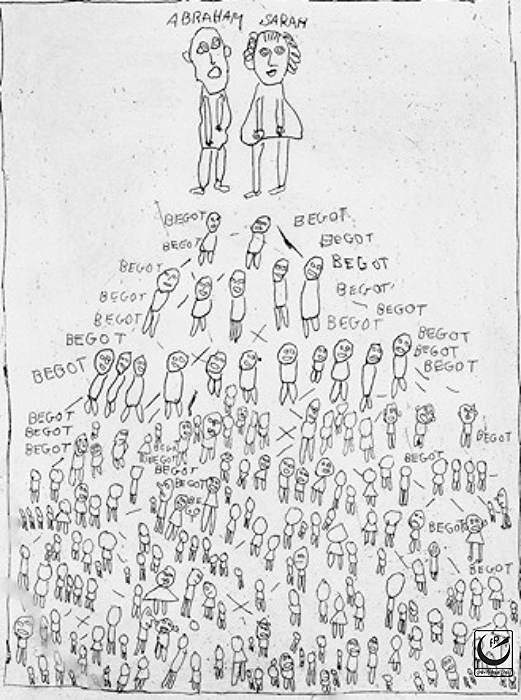

TRACES OF SEPHARAD

(HUELLAS DE SEFARAD),

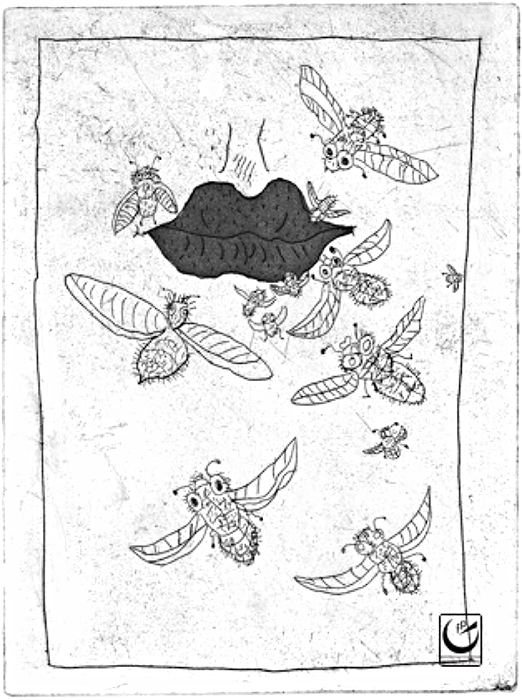

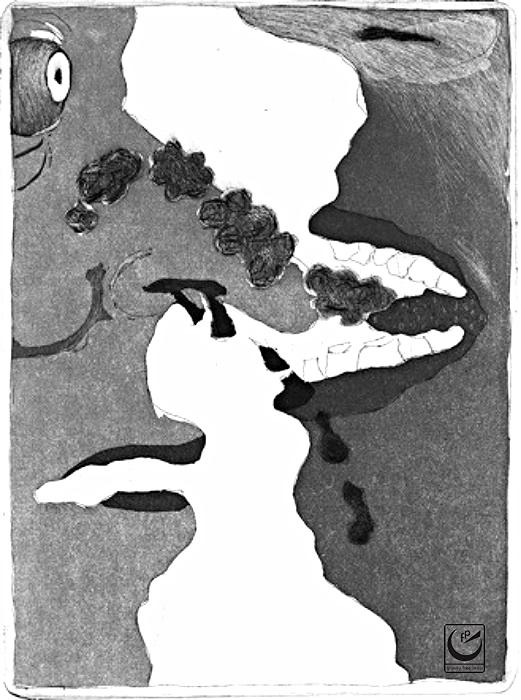

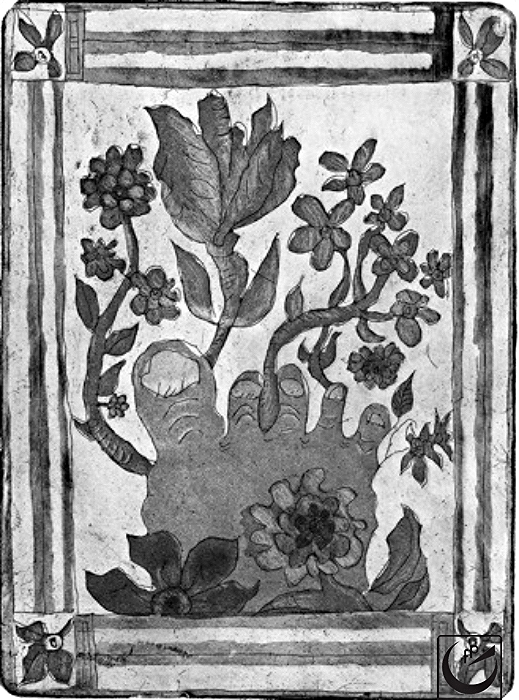

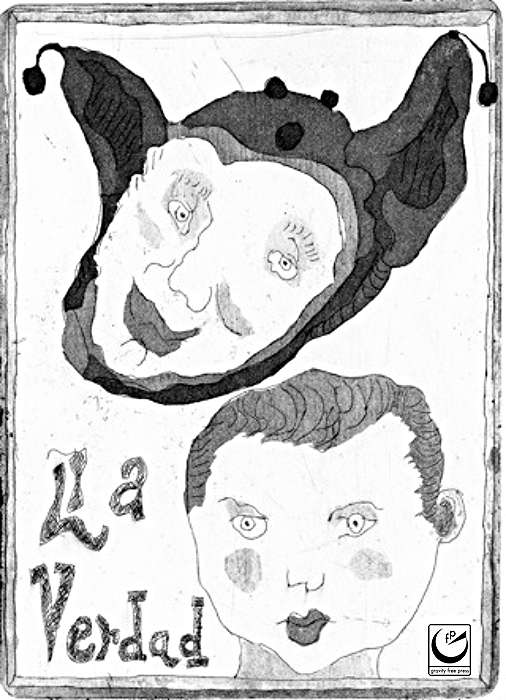

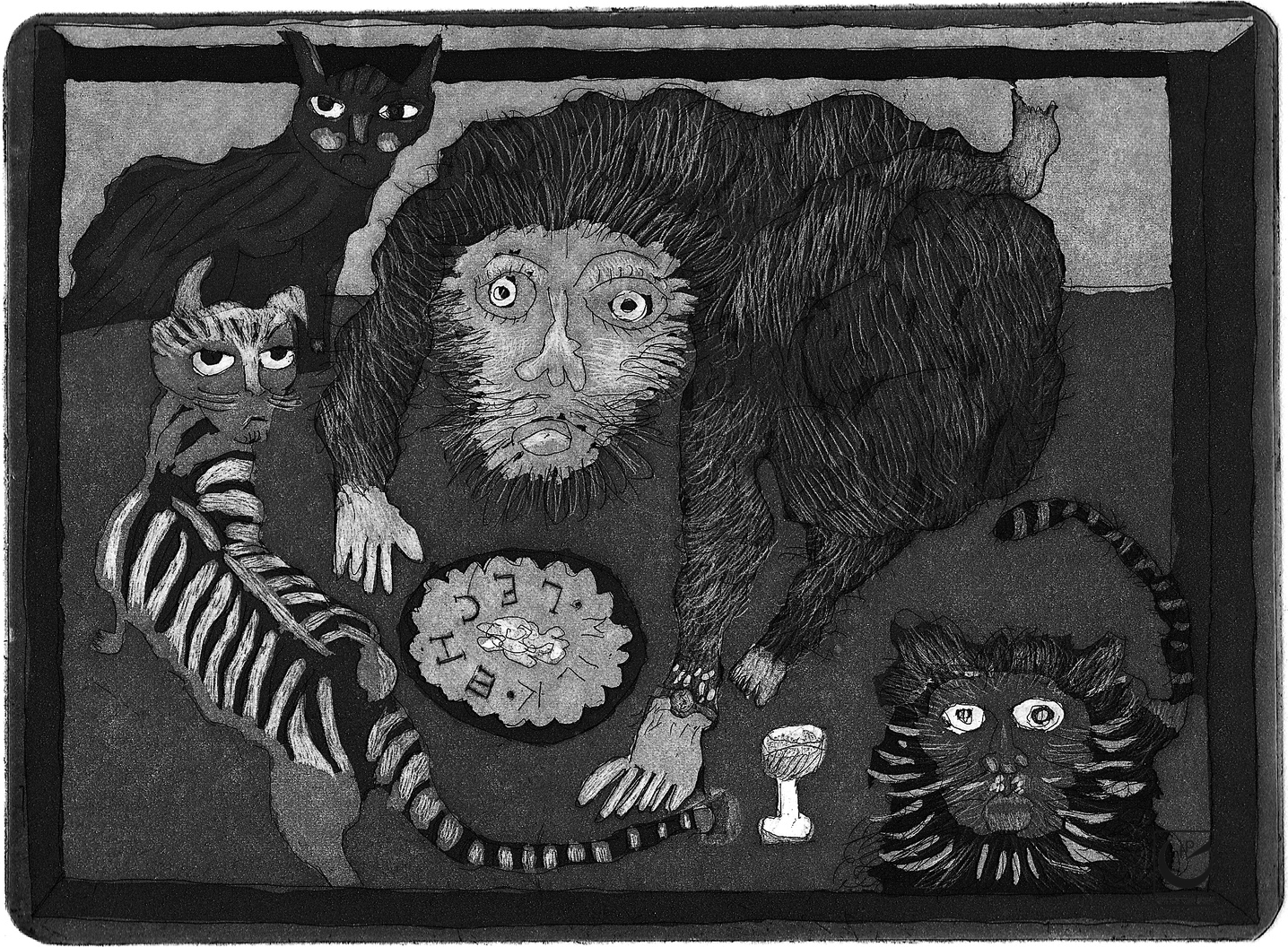

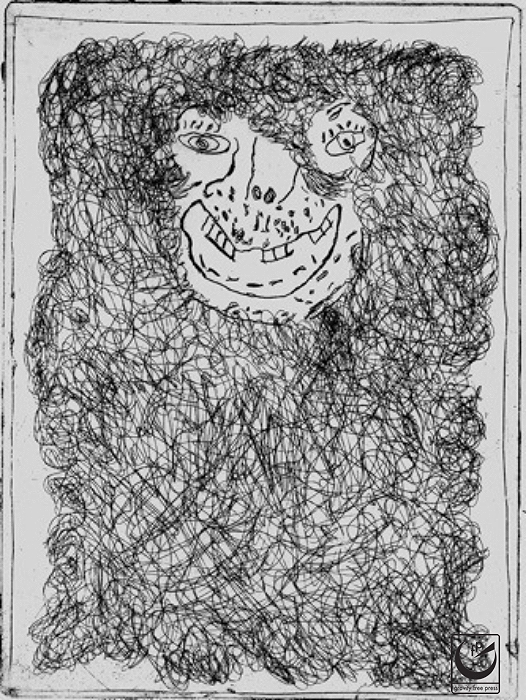

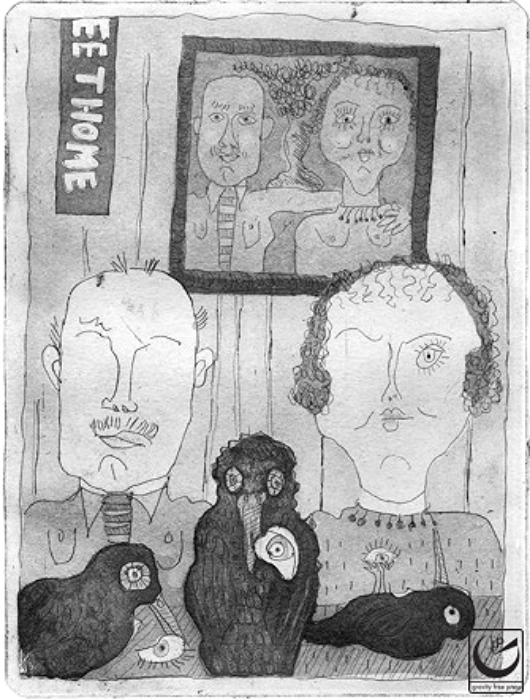

ETCHINGS OF JUDEO-SPANISH PROVERBS

BY MARC SHANKER

with ESSAYS BY

ANTONIO MUÑOZ MOLINA and T.A. PERRY

A Collaboration of art, Literature and scholarship

“Marc Shanker’s haunted art conjures the spirits of Spain and Salonica, via Brooklyn, and in doing so keeps the old alive, as the proverb has it, for the good of the young. And, it needs to be said, for the pleasure of all. With the graceful and evocative essays that accompany the etchings and the proverbs themselves, the book is a gift - to be passed on.”

To purchase a book go to SHOP (GFP)

Etchings

Click on a thumbnail below to see the full image as part of a slideshow, then mouse over image for the Ladino and English title. Get in touch to purchase an original etching.

Sound

Sing along with my grandparents

MY GRANDPARENTS / MIS ABUELOS.

Radio Sefarad Madrid interview here: Marc Shanker: Illustrating Ladino Proverbs

“Having spent their early years in Salonika then under the rule of the Ottoman Turks, sometime around 1917 my grandparents, Riketa (Nona) and Judah (Pop) Pitchon arrived in New York City. They came with their meager possessions, their traditional culture of exile, and their rich proverbial linguistic tradition.

Riketa (Nona) y Judah (Pop) Pitchon, mis abuelos, luego de haber pasado los primeros años de su vida en Salónica, entonces bajo el domino de los turcos otomanos, llegaron a Nueva York alrededor de 1917. Llegaron con sus escasas pertenencias, su tradicional cultura de exilio y su rica tradición lingüística proverbial.”

“Marc Shanker’s ancestors chose to leave the country, or they were left with no choice; they had to leave so quickly that they were barely able to take anything with them and were forced to sell their possessions for next to nothing. But they did take with them something that doesn’t weigh any traveler down and weighs even less when a culture is predominately illiterate. They took their language, along with everything that was preserved by memory when there are few books in existence: their songs and proverbs.”

EXCERPT FROM ANTONIO MUÑOZ MOLINA

“Antonio Muñoz Molina is a Spanish writer laden with prizes and so far scandalously unknown in English. More important, he’s fearless. ”

"De modo que nuestro pasado, el de Marc y el mío, no sólo es común, sino que está igualmente perdido. En mi barrio campesino los judíos vivieron hasta la primavera de 1492: sus hijos cantaban en la calle las mismas canciones, los mayores repetían machaconamente los mismos refranes. No es que los Reyes Católicos deportaran a unos inmigrantes ilegales, visiblemente distintos de la población local en idioma, vestido, costumbres: expulsaron a una parte de su mismo país, a gente que había vivido en aquellos pueblos andaluces y castellanos durante tantos siglos como la población cristiana o la musulmana, que eran parte del vecindario y del paisaje. No fue sólo una injusticia: fue sobre todo una amputación."

"Our pasts, Marc’s and mine, are not only shared, they are equally irretrievable. Jews lived in the rural area where I was born until the spring of 1492; their children sang the same songs in the street, the grown-ups tiresomely repeated the same sayings. The Catholic monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella did not deport a group of illegal immigrants who were visibly different from the local population in their language, dress, and customs; they expelled a part of their own country, people who had lived in Andalusian and Castilian towns for as many centuries as the Christian or Muslim population, people who were part of the local community and landscape. It was not only an injustice, it was an amputation."

Excerpt FROM PROFESSOR T.A. PERRY

"¿Hay pues una cultura o una filosofía sefardí que se expresa en estos refranes? Hay sin duda una impresión de ser marginado por la cultura dominante, pero también un sentido de amor propio compensatorio. Esta reacción ambivalente se expresa también en un hermoso refrán que captó la atención de Shanker. Primero la fuerza de la resignación: Si no es lo que quiero, quiera yo lo que es.

Pero luego la debida retribución judía, lo que podríamos llamar la retardada acción sapiencial: Si pesar hé primero, plazer avré después. Si pesar tengo primero, placer lograré después. ¿Se trata tan sólo de un acomodo estoico?"

"Is there then a Sephardic culture or philosophy expressed in theseproverbs? There is surely a feeling of being marginalized by the dominant culture, but a compensatory sense of self-worth as well. This ambivalent reaction is also expressed in a beautiful refrán that caught Shanker’s attention. First the strain of resignation: Si no es lo que quiero, quiera yo lo que es. If it is not what I wish, may I wish what it is.

But then the Jewish comeuppance, what we might call a wisdom double take: Si pesar hé primero, plazer avré despues. If at first I get pain, I will later get pleasure."